College of Medicine – Tucson diabetes researchers earn distinctions

A team recognized for their high laboratory standards received a grant to develop a device that could eliminate the need for glucose testing and insulin injections to manage diabetes.

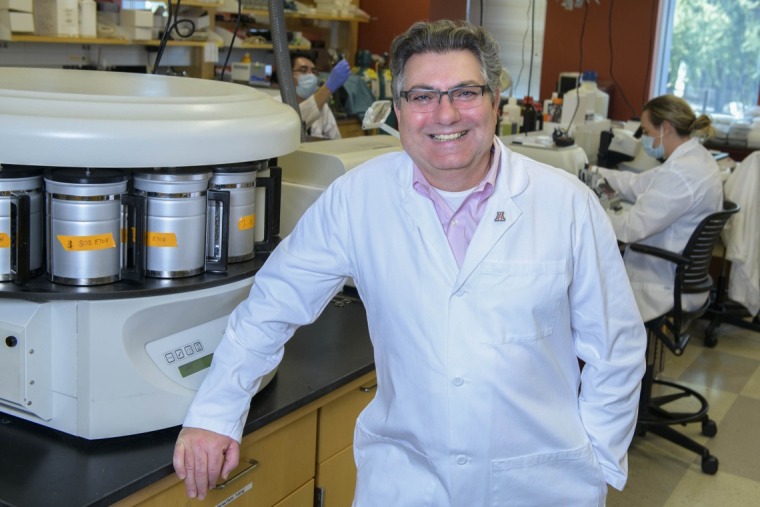

Klearchos Papas, PhD

Kris Hanning

The Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation awarded a team led by Klearchos Papas, PhD, University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson professor of surgery, a $2.65 million grant leading them to clinical testing of a novel oxygen-enabled, implantable pouch containing human islets, pancreatic cell clusters that produce insulin. Testing is expected to take place within three years.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which the pancreas makes insufficient insulin, a hormone produced in the pancreas that regulates blood glucose levels. The disease is currently treated with supplemental insulin delivered by manual injection or through a subcutaneous insulin pump. Patients with Type 1 diabetes need to test their blood sugar levels and receive insulin multiple times a day to ensure their blood glucose stays within the recommended range.

Klearchos Papas, PhD, holds a synthetic nanoporous pouch used in an implantable cell therapy device to provide insulin for Type 1 diabetes patients.

Kris Hanning

The implantable pouch developed by Dr. Papas’ team contains islets that can produce insulin. The team hopes the implant will function like the pancreas, removing the need to test blood sugar levels and receive supplemental insulin.

“Our approach will eliminate big swings in blood sugar that can cause all kinds of problems,” Dr. Papas said. “It controls the blood sugar levels so you don’t have to think about it.”

The current implant prototype uses islets from donors who may not be immunologically matched with the recipient, making it similar to an organ transplant, but without the need for major surgery. This approach requires immune-suppressing drugs to prevent the immune system from attacking the donor cells.

Researchers in the field believe that in three to five years, lab-grown islets genetically modified to be compatible with the immune system could be available in virtually unlimited quantities, removing the need for immunosuppression. Dr. Papas and his team hope clinical testing and validation of the implant is complete by the time lab-grown cells become available so that Type 1 diabetics can benefit from pancreas-like functionality without the potentially harmful effects of immunosuppression.

“There are some similar encapsulation approaches being tested, but nothing really has worked,” Dr. Papas said. “We believe we have that kind of differentiating component that will make it work, so we’re very excited.”

Two samples of a synthetic implantable pouch, which would be infused with insulin-producing cells as a therapy for Type 1 diabetics.

Kris Hanning

The key differentiator achieved by Dr. Papas and his team is the delivery of oxygen to the pouch, in combination with highly specialized membranes. Dr. Papas says oxygen encourages blood vessel growth within the pouch, improving the viability and function of the islet cells within, while the membranes are engineered to promote the growth of new blood vessels near, or within, the device to allow for improved nutrient exchange and a reduced foreign body response, a common issue in the field of implantable devices.

Papas’ work in diabetes research is widely recognized. He directs the UArizona Institute for Cellular Transplantation, which was recently selected by the Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP) as one of 10 human islet isolation centers. The designation qualifies the institute to distribute human islets for research to investigators within the U.S. and around the world. This distinction is bestowed upon a very small number of centers with specialized labs and teams that can isolate, extract and deliver islets to researchers around the world.

“That has put the ICT and the University of Arizona on the map with respect to islet isolation and distribution,” Dr. Papas said. “It enables us to help qualified investigators in need at other institutions by providing human islets for their research, and we pride ourselves in doing so and providing some of the best quality islets.”

The IIDP began at City of Hope in 2002, and it is the largest coordinated effort in the world to provide human islets to researchers. Islets come from organ donors, but they expire quickly outside the body, making them a valuable commodity for diabetes researchers.

Among universities, the University of Arizona joins Columbia University, University of Miami, University of Pennsylvania, University of Wisconsin and Virginia Commonwealth University to earn this distinction. Inclusion in this prestigious group is an important accomplishment for the ICT and the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson.

“The participation increases collaboration with other labs in terms of research resulting in publications and grant submissions,” Dr. Papas said. “That really helps not just the institute, but also the university as a whole. We are very excited about this.”