Kidney Transplant Recipient Grateful for the Gift of Life

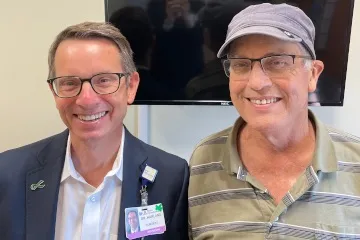

Bruce Byrd (left) meets future physicians at the Class of 2026 White Coat Ceremony.

For Bruce Byrd, 1979 was packed with milestones — most of them good.

“I graduated from college, got married — and found out that I had kidney disease,” he says.

Just weeks after marrying his wife, Patty, and graduating from Western Colorado University, Byrd took a physical for one of his first jobs. The results were unexpected.

“The physical showed some protein in my urine,” he recalls. Follow-up testing revealed that Byrd had Berger’s disease, an autoimmune condition in which a hypervigilant immune system pumps out an excess of antibodies, which clog the tiny filters in the kidneys that remove waste from blood — resulting in kidney failure.

“I remember it vividly,” Byrd recalls. “The doctor said, ‘Bruce, you have kidney disease. It’ll be a while until you need to do anything, so let’s keep an eye on it. Go live life.’”

For almost a decade, Byrd did just that. He and Patty had two daughters and he began a career in commercial/industrial mechanical contracting. But receiving that diagnosis just as he was stepping into adulthood reframed his approach to life.

“It really scared me,” he recalls. “I was worried about supporting my family. That was one of the big motivating factors to be successful in my business. Everybody said to me, ‘You’re very motivated.’ I had a big reason.”

In 1988, his kidneys failed. He started dialysis and was placed on the national UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing) waitlist for a kidney transplant.

“I got my first transplant on Halloween night, 1989, and got 17 years out of that one,” he says. “But kidney transplants don’t last forever. When I turned 50, I received another transplant from a gracious living donor, and that one lasted 14 years.”

Taking care of his gifts

A kidney transplant isn’t over once the surgeon closes the incision.

“It’s a team effort — my family, myself, follow-up by the transplant team and physicians,” Byrd says. “One of the best things you can do is educate yourself as a patient. I consider myself quite experienced on the whole process of transplants and staying alive.”

If a recipient doesn’t take care of their transplant, they risk transplant failure when the immune system notices the “foreign” organ and rejects it.

“Years ago, I met a person who lost his transplant after six months,” Byrd says. “I asked, ‘What happened?’ He said, ‘I got comfortable and quit taking my anti-rejection drugs.’ A lot of people don’t realize that if you do that, it’s going to be very difficult to get another transplant.”

Byrd is passionate about educating fellow transplant recipients about the importance of taking care of their gifts. He used to visit his first transplant center in Denver, on the lookout for anyone who could use some words of encouragement.

“I knew the nurses really well, and would jokingly say, ‘Are there any fresh transplants on the floor?’ I would talk to them about how important it was to take medications on time and be compliant,” he says. “Obviously, with the longevity I’ve gotten out of my kidneys, I’m very compliant.”

Looking for No. 3

In 2021, with the COVID-19 pandemic in full swing, Byrd needed another kidney. To maintain between transplants, Byrd and his wife trained with University of Colorado Health to do in-home dialysis. The intensive training lasted 20 days, from the morning to the mid-afternoon.

“Believe it or not, I enjoyed the training. I learned so much,” Byrd says. After successfully completing it, he was able to spend the next eight months on dialysis — hooked up to a home hemodialysis machine for four to five hours a day, five days a week — in the comfort of his own home.

“I bought a really nice Scandinavian reclining chair to hang out in,” he says. “But I’m a transplant kind of guy. I don’t want to be on dialysis the rest of my life. Unfortunately, over time, the waitlist has grown significantly.”

Byrd was told the current wait time at his hospital in Colorado was four to eight years. Not content to be on dialysis for that long, he did some research into other institutions, and learned that the College of Medicine – Tucson’s clinical partner, Banner – University Medical Center Tucson, had a possible wait time of one to two years. He soon met with Robert Harland, MD, FACS, professor of surgery and surgical director of solid organ transplantation.

“I felt really good about Banner – University Medical Center Tucson as a result of meeting with the team, particularly Dr. Harland,” he says. “He’s very down to earth, great to communicate with, respectful of my knowledge of transplantation — and we both love snow skiing.”

Byrd was curious why the waitlist was shorter than other transplant centers.

“Dr. Harland explained that they look at the patient, they look at the organ, and they take the time to really match those together,” Byrd says. “Where another hospital might turn down an organ, Banner – University Medical Center Tucson and the abdominal transplant team look at the details to see if there is an appropriate recipient who would benefit from transplantation with that organ.”

As a College of Medicine – Tucson faculty member, Dr. Harland is developing additional strategies for decreasing wait time by improving the function of organs that suffer from lack of blood flow during the donation process. This “warm ischemic time” can damage the organ in several ways, including by blocking its small blood vessels.

“We’re working to find ways to circulate blood throughout the donor organ, down to its smallest blood vessels, to prevent blockage,” Dr. Harland said. “Another potential benefit of the technique might be an increase in the time that an organ can be stored before transplantation, allowing organs to be transported longer distances to an appropriate recipient.”

Dr. Harland says keeping the wait list short saves lives.

“The longer you wait to be transplanted, the worse your outcome. Some people die while waiting,” he says. “Figuring out how to better utilize the organs we have available for transplant has been a way to shorten our waiting time. I’m proud that our team is among the Top 10 kidney transplant programs in the country in getting people transplanted faster.”

Welcoming his third ‘gift’

While he waited, Byrd had to be on guard to avoid infection, from COVID to the common cold.

“If you have an infection, you’re not going to get an offered kidney,” he recalls. “You had to lay low and be incredibly careful. I did not stand at the door with COVID test swabs in people’s noses, but it was close to that.”

His caution paid off when he received a call from Tucson early one morning in August 2021: A kidney was waiting for him. The Byrds got on a plane, and that evening he was in surgery.

“It’s working incredibly well,” he says of his new kidney. “My goal is to have this one get me to 80 years old. The key is getting back to a normal and full life, and the gift they gave me has done that.”

Grateful for this gift, Byrd donated to the White Coats and Stethoscopes Campaign for the Class of 2026.

“We’ve got to continue to educate generation after generation of physicians,” he says. “If my wife and I can do just a little something to help students who are coming in, I’m more than happy to help out. It means a lot to me.”

The value he places on educating the next generation of physicians was also reflected in his decision to put himself on Banner – University Medical Center Tucson’s wait list.

“I really like university teaching hospitals. If I can be part of the process, helping pass along the knowledge and expertise to future physicians, I’m all in,” he says. “There are not many patients who have had three kidney transplants, so I get a lot of interesting questions from medical professionals, and I can typically supply good answers. I’ve gained quite the education of kidney disease, dialysis and renal transplants over 43 years. In my next life, I’d like to be a surgeon.”

The new kidney was with him when he traveled to Montana to welcome his newest grandchild in June — unencumbered by a dialysis machine.

“I’m highly focused on having fun and being with my friends, family and spending time with my grandkids,” he says. “I’m playing golf, skiing, mountain biking and living life again. Transplants have allowed me the time to do the things I love.”

Contacts

Anna C. Christensen