To get babies in the ICU back home, feed them right

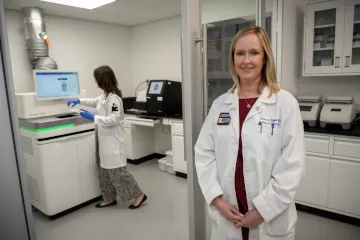

A ‘mistake’ early in her research journey helped Dr. Katri Typpo discover how small changes to nutrition can help babies recover from surgery faster.

A few years ago, Katri Typpo, MD, division chief of Pediatric Critical Care at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson, was in her office, poring over data collected from pediatric patients in the intensive care unit. A statistical abnormality leapt out at her. The data from a few critically ill children were indistinguishable from the data from healthy kids.

“This can’t happen,” she said to herself. “What’s going on here?”

After a deep dive into the data, scrutinizing every detail to make sure what she was seeing was real, she realized she had stumbled upon a potentially game-changing clue that could improve the way children in the pediatric ICU are fed. The trajectory of her research took an unexpected sharp turn.

A nutritional mystery

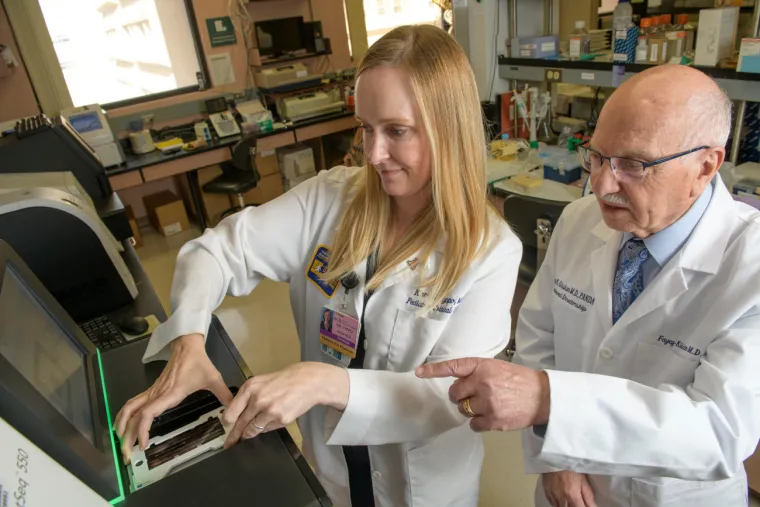

Dr. Typpo had been trained as a physician, but early in her career decided she wanted to do even more to move her field forward. Back in 2014, she approached her department chair, Fayez Ghishan, MD, director of the UArizona Steele Children’s Research Center. She hoped his mentorship would solidify her as a physician-scientist, and together they identified a question in need of an answer.

“There was no standard of how to feed babies when they are critically ill,” Dr. Ghishan said. “When I looked at the literature, there was no consensus on how to feed these babies.”

“The optimal nutrition strategy is unknown,” Dr. Typpo added. “There’s very little prospective, high-quality evidence.”

Focusing on children with congenital heart disease and acute respiratory distress syndrome, Dr. Typpo set out on a mission to learn the best way to feed children in the ICU after surgery. While some children are given nutrition through an IV line that supplies vitamins and minerals to their bloodstreams, others receive foods through feeding tubes that deliver nutrition directly to their stomachs or small intestines.

“If you are sick, people think, ‘Let’s give you IV fluids.’ But the GI tract is really important in recovery,” Dr. Ghishan said. “Dr. Typpo found that if you tube feed them, rather than feed them through IV, they will do much better.”

It turns out that the way babies are given nutrition has a significant impact on the gut microbiome, the collection of microbes that live in our GI tracts. These microorganisms play a pivotal role in maintaining health, including by helping us wring as many nutrients as possible from our foods, holding territory to prevent dangerous pathogens from gaining a foothold, and regulating the immune system.

Babies recovering from surgery are given antibiotics to prevent infections, but the antibiotics also kill off beneficial bacteria. When the GI tract is awash in tube-delivered nutrition, however, the microbiome seems to regenerate more quickly, helping critically ill children return home to their families sooner.

A happy accident

Dr. Typpo’s investigations pitting tube feeding against IV nutrition were well underway. As part of her carefully constructed study design, she made sure the tube-fed children were given a standardized formula with hydrolyzed protein. Then something strange happened.

“The hospital’s formulas changed, so my patients were receiving a slightly different formula,” she said. “I looked at it and said, ‘OK, it’s still hydrolyzed protein. It should be fine.’”

But the data told a different story. The patients receiving the new formula were doing much better than babies receiving the old formula — so much better that Dr. Typpo thought it must be a mistake.

“An ICU microbiome after several days of antibiotics looks very different than a healthy kid playing around outside — but since this formulary change, a couple of patients’ microbiomes suddenly looked more like a healthy kid,” Dr. Typpo recalled. “We dove into the chart to try to understand.”

Drs. Typpo and Ghishan first assumed patient samples must have been mislabeled, or perhaps the data were entered incorrectly. But everything checked out. The cause for the sudden improvement in the tube-fed children was a new ingredient that had been added to the formula.

“That’s how we discovered fructo-oligosaccharide was a likely molecule to preserve the gut microbiome,” she said, referring to a type of fiber that had been added to the formula. “Patients who had received this fiber nearly normalized their gut microbiome, which is not characteristic of an ICU population whatsoever.”

Dr. Typpo was interested in the possible connection between this special type of fiber and unchecked inflammation, which could cause tissue damage or even organ dysfunction in her patients. She hypothesizes that the fiber encourages the growth of bacteria that reduce inflammation not only in the gut, but may also release signals that travel to the lung, reducing inflammation there as well.

She is currently conducting a follow-up study to further investigate the role this fiber plays in critically ill children on mechanical ventilation. Beyond that, she hopes eventually to launch a randomized clinical trial to see if a small dose of the fiber will have the same protective effect in babies who are unable to be tube-fed.

“It was born out of this experimental accident where patients were given fructo-oligosaccharides and we discovered those patients had a more beneficial microbe signature,” Dr. Typpo said. “A lot of times, discoveries happen by accident.”

A meandering path

What began as a small project now spans nearly 20 hospitals across the country, all of which are collecting data and funneling it back to Dr. Ghishan’s lab, which analyzes patient samples so Dr. Typpo can decode the stories they are telling. What started as a mentorship has evolved into a productive collaboration.

“I will always be able to go to Dr. Ghishan, but I won’t ask him the nitty-gritty details about an experiment because now I understand how to do those things,” she said.

“This is a physician who transformed to become a physician-scientist, taking what we did together to the next level,” Dr. Ghishan said. “All of a sudden, she is a highly respected investigator in nutrition, the gut microbiome, and how to feed babies. Now we are working to set the standard for the country.”

As the attending intensivist at Banner – University Medical Center Tucson and Diamond Children’s Medical Center, Dr. Typpo hopes her ongoing research will eventually guide her colleagues in the pediatric ICU to feed babies in a way that supports a healthy gut microbiome, which could in turn decrease inflammation, protect their organs and shorten their hospital stays.

“In the future, it will be rewarding to actually make care better for the kids in the ICU, and to confidently tell a parent, ‘We know we’re feeding your kid in the best way possible,’ so they can be home with their families and healthy and well,” she said.

Dr. Typpo is grateful for the “mistake” that pointed to the special fiber in the babies’ formula.

“The line of research isn’t straight,” she said. “You find things that raise new questions and lead you down another pathway. You let the data be your guide, and it takes you down this meandering path.”

Photo credits (from top to bottom): Kris Hanning (UArizona Health Sciences), Darci Slaten (Department of Family & Community Medicine), Noelle Haro-Gomez (UArizona Health Sciences), Kris Hanning (UArizona Health Sciences)