Meet Alex Singh Parmar: 'I want to spark change'

At the end of the summer, Alex Singh Parmar will be the first University of Arizona student to receive a Bachelor of Science in Medicine from the College of Medicine – Tucson. He has applied to a graduate-level program at the college to build his research skills, but his ultimate goal is to attend medical school and serve his community as a physician.

A first-generation Punjabi American, Parmar's path toward medicine began when he was a child. His mother supported the family as a hardworking surgical nurse, and his father was disabled with rheumatoid arthritis. Parmar was thrust into a caretaker role.

"Growing up, being a caretaker for a disabled father and also my younger brother was a big responsibility to hold on my shoulders," he recalls. "I was always with him at appointments, caretaking, pushing his wheelchair. Seeing the things that physicians do really opened me up to the world of medicine and the types of care patients deserve. It brought light to how as a provider I could improve the patient experience."

Parmar believes the patient experience can be improved in two ways: by instilling physicians with increased cultural dexterity to navigate the intricacies of their patients' care, and by making changes to the system that would protect people like his father from falling through the cracks.

"His diagnosis was delayed because of cultural and language gaps. They told him he had depression and he should go home and see if he could fix his mood. Unfortunately, it was bigger than depression, and in India, care wasn't the same," Parmar says. "That experience is what pushed me into medicine, and 25 years later, here I am."

'Developing as a Spanish speaker'

Parmar's friends played another big part in shaping his understanding of patient experiences. As a student at University High School, whose student body was majority Latino, Parmar forged friendships that opened another language to him — and gave him the background to better understand the social drivers of health disparities.

"Hanging out with friends, listening to Spanish music, wanting to understand what's going on, being acclimated with their families and understanding the culture — I just picked the language up very quickly," he says.

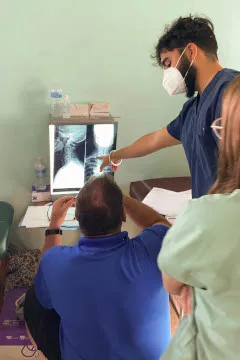

In college, Parmar participated in FACES Conversantes, which offers an undergraduate course in medical Spanish. He applied what he learned at Commitment to Underserved People (CUP) Clinics as a medical interpreter.

"At first I lacked confidence, but working at these clinics bolstered me," he says. "You're tossed in, and you realize, 'Hey, I can speak Spanish. I can communicate with people!' That experience has been huge for me in developing who I am as a Spanish speaker. I'm learning something new about Spanish every single day."

When the pandemic shut everything down, Parmar took one of the few available opportunities to get hands-on experience in his chosen field by working at the drive-through vaccination clinics set up at the University of Arizona mall. As a medical interpreter and scribe, he saw first-hand some of the barriers faced by people who do not speak fluent English.

"The sign-up sheets and screening questions were only in English. In situations where interpreters might not be available, we could have easily had the page in Spanish. Just because you don't speak English, does it mean you don't deserve care?" he asks. "As providers, we can do as much as we can one-on-one with the patient, but we need to further impact the roots of these problems at systemic and organizational levels. I want to be a provider who can spark further change."

'An immersive experience'

Parmar was volunteering at a CUP clinic when he first heard about the BS in Medicine program. It would be a year until the program started to enroll majors, but he took a peek at the proposed curriculum. He liked the broad course selection, which he recognized would prepare him for many possibilities in his chosen field, and got a head start on the coursework for that major without delaying his graduation.

One such class was FCM 296, Careers in Medical Health Sciences, which uses a learning methodology called case-based learning, a central component of the degree program in which students are taught by many different health care professionals who present real-world medical cases.

"I thought this class was perfect for people who want to go into the medical field but might not know what they want to do. They created an immersive experience, exposing you to a career path that you may decide to pursue, making sure students are getting a better understanding of what's ahead," Parmar says.

Paul Gordon, MD, MPH, co-director of the Bachelor of Science in Medicine program and professor of family and community medicine, co-teaches the Careers in Medical Health Sciences class, which he designed as a way for students to see patient cases through multiple perspectives.

"Each week, students examine how they would care for a patient through the lens of one of nine different professionals — a social worker, a nutritionist, a nurse, a doctor, etc. They're really getting an idea of the breadth of the teamwork involved in caring for patients," Dr. Gordon says. "Patients are represented through the lifecycle, starting with a newborn whose mom has used drugs, a child with cerebral palsy, and we end with an elderly person whose adult children want to put them in a nursing home."

In addition to learning more about the collaboration involved in medicine, Parmar also appreciates that the major enables interaction with medical students and faculty members, and especially that so many classes are taught by practicing clinicians.

"They can give you personal anecdotes and stories showing how outside of the interaction that you have with the patient, there's so much going on," Parmar says.

"There are more practicing clinicians teaching in this undergraduate curriculum than any other undergraduate curriculum I'm aware of," Dr. Gordon adds. "We have MDs teaching in the first two years. We are picking our teachers to be sure we have the best and the most engaging and energizing."

'I'm making a positive impact'

The BS in Medicine includes basic science prerequisites and core courses, and currently has four areas of emphasis: medical technology, basic medical science, medicine and society, and integrative and practice-focused medicine. Dr. Gordon says not many universities offer a BS in Medicine, and no other medical schools offer it, making the College of Medicine – Tucson "pretty unique." The program has exceeded its first-year enrollment goals with 225 students.

Parmar would recommend the BS in Medicine major to anyone who is interested in a career in health care.

"This is a perfect major for anybody with any ambition or pursuit into medicine," he says. "They can really get to know what medicine is about, and then decide, 'Is this for me?' It's a great environment for anybody coming out of high school or community college and being thrown into the fray."

Dr. Gordon says the degree is designed to pique students' interests in a range of fields.

"Each of the health professionals who are teaching are so passionate about their discipline," Dr. Gordon says. "I have to imagine each week the student is thoroughly confused — 'I want to be a nutritionist,' and the next week, 'I want to be a physical therapist.' I think that's great!"

Parmar says his coursework drove home that health care is a team practice, and he has enjoyed learning about the teammates he hopes to rely on someday. But he has never wavered from his goal to practice medicine.

"I want to be the provider my dad didn't have," he says. "My goal is to serve the community I was raised in, knowing at the end of the day that I'm making a positive impact in the world."

Contacts

Anna C. Christensen