Athletes team up with the Valley Fever Center for Excellence

Athletes show us that everyone is susceptible to Valley fever, caused by a fungus that lurks in the dirt of the U.S. Southwest. But they also show us that knowledge is power, and that early diagnosis can make a difference.

They came from far and wide to represent the University of Arizona on the field. Some played indoors, but others were exposed to the elements, such as the student-athletes charging across yard lines or chasing personal bests on the track.

Nicole Stern, MD, MPH, a University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson Class of 1998 graduate and sports medicine team physician at the U of A Campus Health Service, wondered if those student-athletes playing outdoors — and breathing in the dusty Tucson air — were more susceptible to an endemic fungal disease.

“I helped cover several of the NCAA Division I sports as a team physician. My hypothesis was that we would see an increased number of scholarship athletes with cocci infections,” she said, referring to coccidioidomycosis, more commonly called Valley fever, “especially the ones who play outdoor sports.”

To test her hunch, Dr. Stern performed a study. Reviewing Valley fever test results from Campus Health from 1998 through 2006, she found that 305 students had been diagnosed with the infection — and scholarship athletes were four times more likely to be diagnosed with Valley fever than the rest of the student body.

“I was surprised at how much higher the rate in scholarship athletes was — I knew it would be higher, but not that much,” she recalled. “I was also surprised there was no difference for those playing outdoor versus indoor sports.”

Diving deeper into this difference, Dr. Stern discovered student-athletes were tested for Valley fever five times more frequently than students from the general population — which also surprised her.

“Growing up in Tucson, I knew about the disease at a young age — I remember getting cocci skin testing done as a routine thing, but now that is not really done anymore,” she said. “As a sports medicine specialist, I was intrigued by the number of scholarship athletes who had cocci.”

Athletes speak out

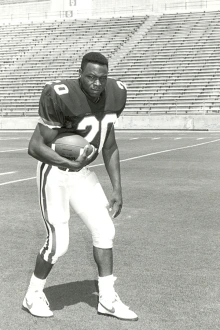

Michael Bates is a University of Arizona Athletics Hall of Famer whose speed took him from the fields of Amphitheater High School to the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, where he won bronze in the 200-meter sprint. He went on to star as a wide receiver and kick returner for the Wildcats, later joining the NFL.

“Being a native, growing up here and being an athlete, you don’t think about certain things — and I didn’t think about Valley fever until I got it,” Bates said.

Unsuspecting of the impact it would later have on his health, Bates wasn’t diagnosed until his 50s — about two years ago. His case was a serious form known as disseminated cocci, which had spread to his spine, requiring lifelong antifungal therapy.

Although symptoms appeared months earlier, the diagnosis was difficult to pin down. The flu-like symptoms overlapped with other conditions such as diabetes, which he initially thought his illness could be tied to. It wasn’t until he became immobile that his wife, Brittany Bates, rushed him to the emergency department. At first, doctors suspected tuberculosis, then cancer.

Further diagnostic testing, including lung and heart biopsies, revealed the true cause: Valley fever.

“I know we hear about it, but there’s so much more that could be known,” Bates said.

Now, he’s turning his experience into advocacy by sharing his story for increased awareness and encourages regular testing for earlier diagnoses and better outcomes.

“Valley fever is real, it’s serious, and it doesn’t care if you’re an athlete or not. My hope is that by sharing my story, more people will ask the right questions, get tested sooner and stay healthy,” Bates said.

Many other athletes have had problems with Valley fever.

Athletes Affected by Valley Fever

Baseball

1972: Cincinnati Reds catcher Johnny Bench contracted Valley fever, requiring chest surgery.

2009: Arizona Diamondbacks’ Conor Jackson lost 30 pounds and missed most of the season due to Valley fever pneumonia.

2012: New York Mets’ Ike Davis contracted Valley fever, affecting his performance for months.

Basketball

1986: Johnny Moore (San Antonio Spurs) contracted Valley fever meningitis, interrupting his career for three seasons.

2000: Loren Woods (U of A) missed the NCAA Tournament due to Valley fever requiring back surgery.

2013: Jermaine Marshall (Arizona State) was sidelined by Valley fever.

Football

2020: Sterling Lewis, after a successful career at the University of Arizona, died of Valley fever in Texas at age 32.

Soccer

2023: John Stenberg contracted Valley fever while helping Phoenix Rising win its first United Soccer League championship, still recovering in 2024.

Golf

2002: Gregory Kraft developed Valley fever after competing in the PGA Tucson Open.

2007: Shane Prante lost 40 pounds and was incapacitated by Valley fever.

2011: Charlie Beljan developed Valley fever that spread to his hand, requiring surgery.

A history of Valley fever discovery

Valley fever is caused by fungal spores found in soils of the Southwest — California, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas and parts of Mexico. Most people who didn’t grow up here have never heard of Valley fever.

John Galgiani, MD, has been studying Valley fever for nearly 50 years. In that time, he has been hard at work to raise awareness, improve diagnostics and treatments, and help develop a vaccine that may someday prevent it.

Kris Hanning

“Knowing what Valley fever is and recognizing its symptoms is everyone’s best defense,” says John Galgiani, MD, founding director of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence, now in its 30th year since Arizona Board of Regents’ approval. “Simply living here puts you at risk of getting infected — it’s not just people who are involved with dusty jobs or other activities involving dirt. People in my clinic are a cross-section of the general population. Although it makes sense to avoid dust storms, infections can occur even when there aren’t windy conditions — fungal spores are very small and stay suspended in the air for extended periods of time.”

Typical symptoms range from chest complaints like cough, pain, shortness of breath and sputum production. Muscle and joint aches, rashes and severe fatigue, often lasting for weeks or months, are also common. Patients with pneumonia due to Valley fever might be treated with ineffective antibiotics and undergo imaging and other procedures that could have been skipped if Valley fever testing had been done in the first place. Patients could start antifungal treatment sooner, possibly avoiding more severe infection from disseminated cocci.

Diagnosing Valley fever requires a blood test, but physicians and other health care providers frequently do not test for it — even in areas where the infection is common.

“That’s where awareness about Valley fever becomes important,” said Dr. Galgiani. Arizona Department of Health Services research has shown that people who already knew about Valley fever are diagnosed sooner than those who didn’t, simply because they request testing. “Until a vaccine is available, you can’t protect yourself — except with knowledge and awareness.”

Arizona is the only endemic state with a university center devoted to managing this disease. The Valley Fever Center for Excellence is working with its clinical partner, Banner Health, to test for Valley fever whenever possible. In 2018, Banner adopted the Center’s testing recommendations, and those rules have been making a difference. In 2020, Banner’s many urgent care clinics in Arizona were only testing 2% of pneumonia patients for Valley fever. Now, testing happens nearly half of the time.

“Some patients who have pneumonia already have another explanation for what’s causing it,” Dr. Galgiani said. “I don’t think the testing rate should be 100% — a good target would be 70%, and that’s what we are aiming for.”

The best offense is a good defense

Besides leading to a precise diagnosis as early as possible, the more you know about Valley fever the more you see opportunities for improving its management. Current diagnostic tests, although very specific, are done in reference laboratories — meaning that test results are not available for days if not weeks.

“If we had a point-of-care test, a diagnosis could be made immediately. It would be a gamechanger,” Dr. Galgiani said. “You’d come in and see if you have Valley fever, just like flu or COVID, and you’d get precise treatment.”

Another challenge is that current antifungal drugs only suppress infections — they don’t cure them. These drugs are useful, sometimes even lifesaving, but they need to be taken for months, years or, for some people, the rest of their lives.

“There is no cure,” Dr. Galgiani said. “Current treatments just put the fungus to sleep, but if you stop treatment, it can come back.”

“It’s not something that just goes away,” Bates said. “I still deal with pain, I still wake up in sweats and we are still learning alongside Dr. Galgiani, who has played a major role in teaching and guiding as we figure out the best way to manage my treatment.”

Lisa Shubitz, DVM, a research scientist at the Valley Fever Center for Excellence, has focused her research on developing a vaccine for Valley fever, along with studying the epidemiology of the disease in canines.

Noelle Haro-Gomez/University of Arizona Health Sciences

In a breakthrough for the field, Valley Fever Center for Excellence scientists discovered a vaccine, which has been licensed by a commercial partner, Anivive Lifesciences, to develop a veterinary product to protect dogs — which is quickly heading toward approval and could be available within a year. Last year, Anivive received a contract from the National Institutes of Health to continue the vaccine’s development for humans, which would make it the first vaccine to protect humans against a fungal infection.

Even if better treatments and a human vaccine become a reality, awareness remains the best defense. Dr. Stern, now a team physician at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and urgent care clinical department head at the Sansum Medical Group Santa Barbara, urges both patients and health care providers to learn about the disease.

“It is so important to recognize Valley fever as a possible cause of pneumonia and other skin or systemic illnesses, especially for those visiting the endemic area for a short time,” she said. “Clinicians around the country should keep coccidioidomycosis in their differential diagnosis, always!”

Athletes aren’t the only ones who need to know about Valley fever. It’s everyone. Together, researchers at the Valley Fever Center for Excellence and physicians around the country are working toward a future in which the effects of the disease recede like dust after a storm.

Learn more about the Valley Fever Center for Excellence at their website.